Representation also demands effort. Writing credibly about Indian cinema requires engaging with films across languages, seeking diverse critical sources, and acknowledging the limits of one’s viewing and access. Tokenism- adding one non-Hindi film to an otherwise Hindi-heavy list- does not solve the problem. It merely disguises it.

Social media is full of definitive lists: "Best Of Indian Cinema", "Top Indian Films", "Must-Watch Indian Series", "The 50 Best Indian Movies of All Time." They are click-friendly, shareable and written with the confident tone of authority.

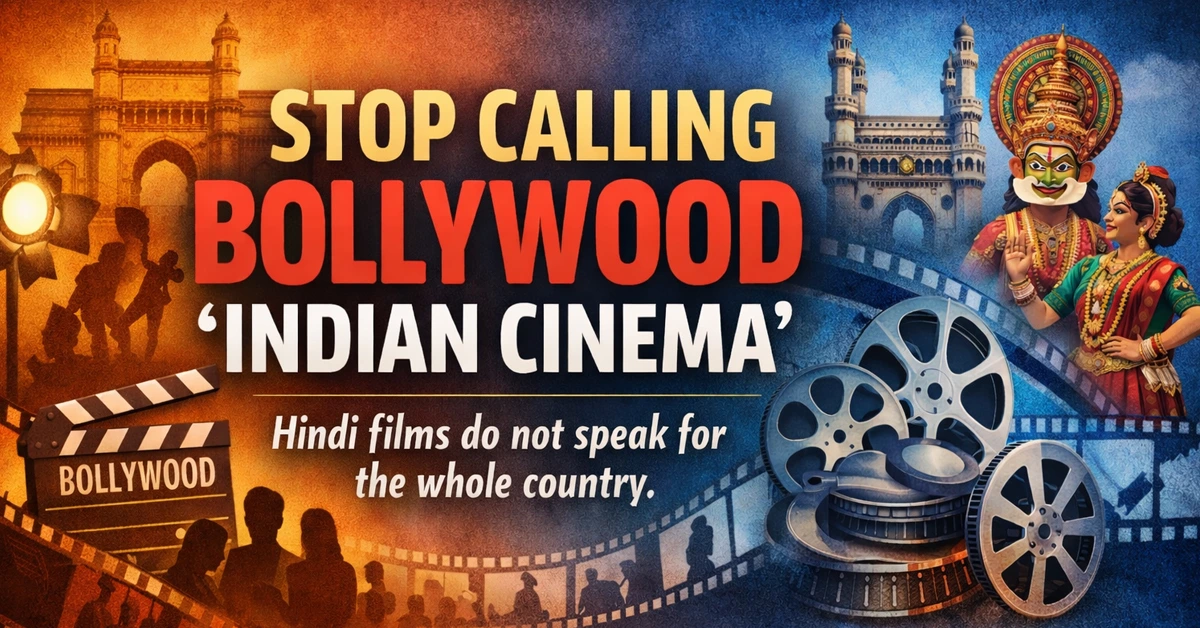

Though the lists seem simple, harmless and should not call for any controversy, there is, however, a problem and this problem is simple: most of these lists do not actually represent Indian cinema. They represent Hindi cinema. If not entirely, then overwhelmingly so- often 90 to 95 per cent of the selections are in Hindi. That is not coincidence; it is a pattern. And it is misleading.

India is not a monolingual nation. It never has been. It is a country shaped by multiple languages and cultural traditions- Tamil, Telugu, Malayalam, Kannada, Bengali, Marathi, Gujarati, Assamese, Odia, Punjabi and many more- each with its own cinematic history and its own way of telling stories. Indian cinema, by definition, is plural. Reducing it to one language is not simplification; it is erasure.

There is also a fundamental constitutional reality that is conveniently ignored in popular discourse. India does not have a single national language.

Hindi is an official language of the Union, used largely for administrative purposes, but it is not the national language of the country. To repeatedly present Hindi-language cinema as Indian cinema is therefore not just culturally inaccurate but intellectually dishonest.

Why does this matter? Because such lists shape perception. For many readers- especially younger audiences and international viewers- these articles and reels become entry points into Indian cinema. When they are told, directly or indirectly, that Indian cinema begins and ends with Bollywood, entire industries are pushed to the margins. Films in other Indian languages are treated as outliers, "discoveries" or exceptions, rather than integral components of a national cinematic tradition.

Bollywood's dominance did not emerge in a vacuum. The Hindi film industry has historically enjoyed greater capital, wider distribution, a powerful star system and stronger global visibility.

For decades, it was the most accessible face of Indian cinema. But access should not be mistaken for authority. Visibility does not automatically confer representational legitimacy.

The persistence of Hindi-centric lists also reflects a deeper problem: critical laziness. It is easier to compile a list drawn almost entirely from Hindi films because the ecosystem is familiar- stars are recognisable, promotional material is abundant, and the reviewer is rarely forced to step outside their comfort zone. But convenience cannot be an editorial standard. When a piece claims to map Indian cinema and delivers only Bollywood, it fails its basic premise.

ALSO READ | My 5 Best Hindi films Of 2024

Even as films from Assamese, Bengal, Malayalam, Tamil, Telugu and other industries have gained national and international attention in recent years, the language of coverage remains telling. These works are often described as "regional breakthroughs" rather than simply important Indian films. The qualifier never quite disappears. The centre remains fixed; everything else is expected to orbit it.

This is where responsibility comes in- especially for influencers and critics who command large audiences. If a list focuses primarily on Hindi-language cinema, it should say so clearly. Call it "Top Hindi Films" or "Best of Bollywood".

There is nothing wrong with specificity. What is wrong is using "Indian" as a catch-all while quietly excluding most of the country’s cinematic output.

Watch More

Representation also demands effort. Writing credibly about Indian cinema requires engaging with films across languages, seeking diverse critical sources, and acknowledging the limits of one’s viewing and access.

Tokenism- adding one non-Hindi film to an otherwise Hindi-heavy list- does not solve the problem. It merely disguises it.

None of this is an attack on Hindi cinema. Many Hindi films are significant, influential and artistically accomplished. The issue is not quality; it is categorisation. Precision matters in criticism. Language matters. And calling something "Indian" carries responsibility in a country as culturally and linguistically complex as ours.

If we continue to allow Hindi cinema to stand in unquestioned for Indian cinema, we will keep misleading readers and flattening a rich, layered cinematic landscape into a single, convenient narrative. Indian cinema deserves better. So do its audiences- both from the country and also from outside.

ALSO READ | Talent Vs. Privilege: Are We Supporting The Right Films?

Partha Prawal (Goswami) is a Guwahati-based journalist who loves to write about entertainment, sports, and social and civic issues among others. He is also the author of the book 'Autobiography Of A Paedophile'.