There is a basic yardstick for any security policy in a plural democracy: Does it reduce fear across communities, or does it increase fear for at least one group? If even one vulnerable minority — whether defined by religion, language or birthplace — reports feeling less secure because of the policy, the design has failed. Public policy must be judged by its effect on social cohesion and on the rule of law.

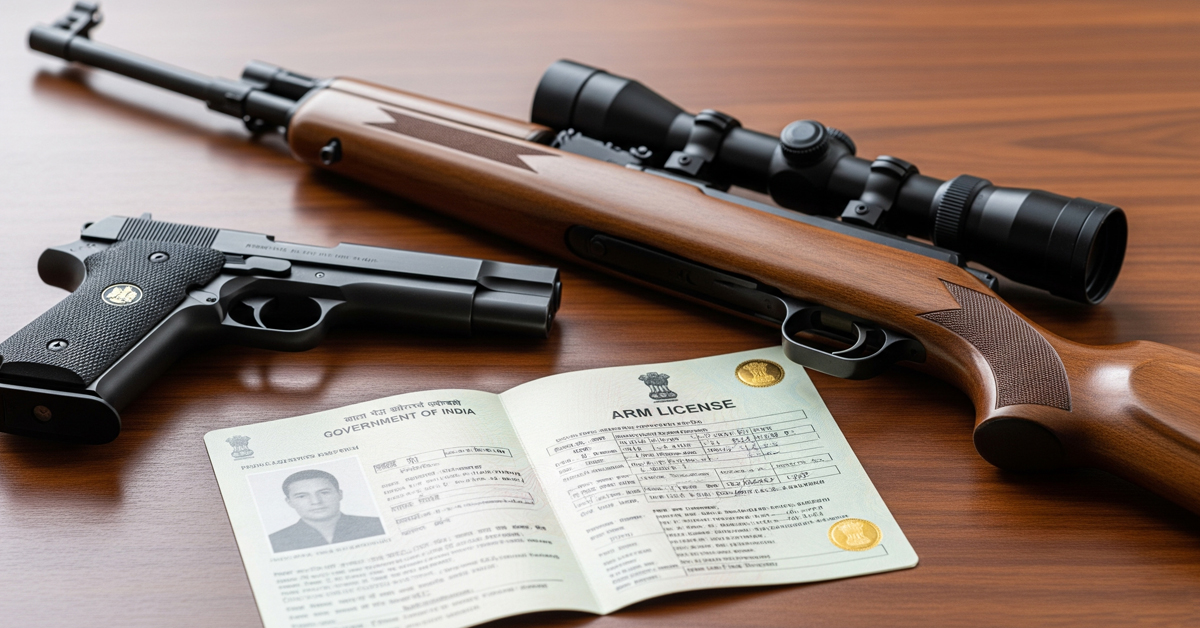

The state cabinet on May 28, 2025, approved the Assam Arms-License scheme, to provide arms licences to what the state describes as “original inhabitants and indigenous Indian citizens” living in vulnerable and remote parts of the state.

The government has said the policy targets districts where local communities feel insecure and has framed the move as an instrument of self-defence; the administration is now preparing an online portal to process applications.

Those are the procedural facts. The deeper question — and the public duty of any responsible government — is whether legalising more private gun ownership solves the problem it names, or simply transfers lethal capacity from trained, accountable forces to private hands.

In Assam’s current political and social context, the balance of evidence points strongly to the latter.

What The Scheme Says — And What It Will Do

Public reporting and the government’s own service page describe a mechanism that fast-tracks licence applications for people who qualify as “indigenous” and who reside in routes, pockets and districts denoted by the administration as “vulnerable.”

The state has listed districts such as Dhubri, Nagaon, Morigaon, Barpeta, South Salmara-Mankachar and Goalpara, among others, as examples of the areas envisaged under the policy.

Officials say licences will follow identity checks, police verification, threat assessments and periodic review; licences will be non-transferable and liable to cancellation if misused.

A portal to facilitate applications has been readied and may go live imminently.

The government excludes inter-state border tracts (with Meghalaya, Arunachal Pradesh, Mizoram and Nagaland) from the scheme, and officials emphasise legal safeguards and monitoring. Yet administrative safeguards are not the same as social consequences; a system that makes firearms available to politically or communally marked categories of people is liable to reshape local power relations overnight.

The Stated Rationale — And Its Political Freight

Chief Minister Himanta Biswa Sarma has repeatedly presented the policy as a response to local insecurity — including anxieties about illegal migration from across the Bangladesh border — and to historical grievances of indigenous communities that feel threatened in areas where Bengali-origin Muslim populations are significant.

At the same time, the state is pursuing other moves — expedited deportations and renewed emphasis on the NRC and related mechanisms — to address perceived immigration pressures.

Such a combination of measures — targeted policing, immigration drives and now the selective arming of citizens — cannot be read as neutral administrative choices. Policy is political by design, and the signal it sends matters as much as the paperwork that accompanies it.

Opposition, Civil-Society Alarm And The Risk Of Communalisation

Political opponents and civil-society groups have been vocal. The Congress and regional parties have described the measure as divisive; local opinion pieces, editorials and non-governmental commentators have warned it risks communalising security and encouraging vigilantism.

Several opposition leaders have framed the policy as likely to stigmatise communities of Bangladeshi origin and to invite social policing by armed civilians, with predictable consequences for minorities and migrants.

These objections are not hypothetical. When a government defines eligibility for lethal capacity along identity lines, it hands political actors a powerful lever: the ability to declare who is an insider and who is an outsider, and — implicitly — who may be viewed as a legitimate target of force.

The Manipur Lesson — A Proximate Warning

Assam’s debate should be read against what occurred in neighbouring Manipur from 2023 onwards, where ethnic confrontation escalated rapidly into armed conflict.

ALSO READ | How India Failed Manipur: The 2023 Violence And Its Aftermath

Reporting and independent investigations showed how arms — both looted and locally sourced — were used to entrench territorial claims, create militia zones and perpetrate atrocities; thousands were displaced and communal trust was shattered.

The Manipur experience demonstrates how the ready availability of weapons, combined with weak or partisan enforcement, can convert local grievances into long-running cycles of violence.

That is not an argument that Assam should do nothing; it is an argument for doing the right things. The Manipur experience is a real, recent case study of rapid escalation. Any move that increases the number of legally held guns in mixed districts must be assessed through that lens.

Evidence From Public-Health And Criminological Research

The international literature on firearms is clear on a basic point: more guns in private homes tend to produce more firearm deaths, not fewer.

Systematic reviews and epidemiological studies find substantial associations between household firearm access and higher risks of homicide, suicide and unintentional firearm deaths.

Safe-storage rules, training and vetting reduce some risks — but do not remove the well-documented mortality multiplier that accompanies widespread gun availability.

Public-health thinking treats firearms as an environmental risk factor; from that perspective, relaxing barriers to access is a predictable driver of harm.

In Assam’s social topology — where communal tensions exist, where grievances over land and identity are live, and where state capacity varies — the epidemiology of guns argues strongly against broad civilian armament as a policy to reduce insecurity.

Practical Alternatives The State Should Pursue

If the cited problem is illegal immigration and porous borders, the answers are administrative and security-sector, not civilian armament. Concrete alternatives include:

Finish and transparently implement legal processes for citizenship adjudication and deportation — with legal aid, review mechanisms and international engagement where necessary. Arbitrary enforcement fuels panic and vigilantism.

Strengthen policing and quick-reaction capacity in affected districts: more patrols, better border intelligence, fast response units and community liaison officers, with independent oversight.

Invest in community policing and conflict-prevention programmes that rebuild local trust, rather than signalling that force is the first option.

Tighten arms regulation and supply-chain security to prevent thefts and trafficking from state armouries and private stocks — an issue made plain in the Manipur crisis.

The state’s duty is to make institutions credible again. Deputising civilians with firearms is a shortcut with high human costs.

A Simple Test Of Legitimacy

There is a basic yardstick for any security policy in a plural democracy: Does it reduce fear across communities, or does it increase fear for at least one group?

If even one vulnerable minority — whether defined by religion, language or birthplace — reports feeling less secure because of the policy, the design has failed. Public policy must be judged by its effect on social cohesion and on the rule of law.

Conclusion: Law, Not Licences

Assam government says it seeks to protect. That is an uncontroversial aim. But protection provided by licensed guns is protection by private force; it is fragile, reversible and liable to be repurposed.

History, public-health science and recent regional experience counsel against treating firearms as a scalable public-policy fix for deep governance problems.

If the state’s real aim is to make communities safe, it must choose institution-building over informal armament: better policing, impartial justice, improved border surveillance and transparent handling of immigration issues. Anything less risks exchanging a brittle peace for a permanent, armed unease.

Assam can protect its people without arming them. The state should abandon the Assam Arms-Licence Scheme and instead deliver the harder work of rebuilding public security and shared citizenship.

ALSO READ | The Grim Fate of Assamese Speakers!

The Story Mug is a Guwahati-based Blogzine. Here, we believe in doing stories beyond the normal.